Addison × Sézanne: Inside a Rare Collaboration Between Two Three-Star Kitchens

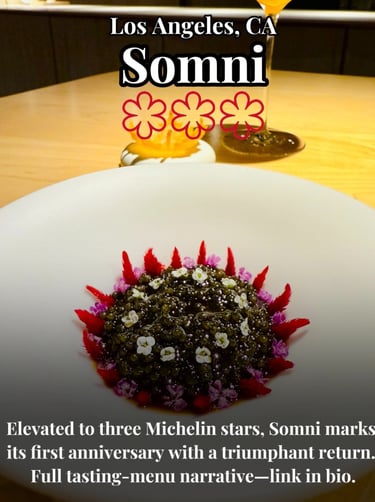

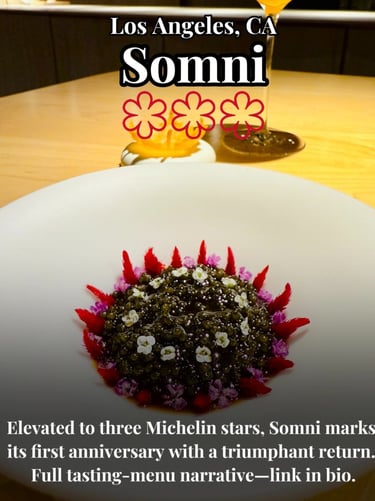

MICHELINFEATURED

For two evenings only, Sézanne—Tokyo’s radiant three-Michelin-star sanctuary, consistently ranked among the very best in Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants—collaborated with California’s three-Michelin-star pioneer, Addison by Chef William Bradley. Two visionaries, Chef William Bradley and Chef Daniel Calvert—each crowned with the highest three-knives distinction by The Best Chef Awards—chose to step beyond the perfected worlds they command individually, and together created a collaboration menu that belonged to neither kitchen alone. What follows is not a critique, but a reverent pilgrimage: a course-by-course immersion into a menu that existed for two nights and two nights only. Written from a Japanese perspective, this narrative offers cultural nuances rarely articulated in broader culinary articles—the backstage story of Olive Wagyu, the profound, almost reverential unfolding of the ankimo bite, and countless other subtleties that invite the same quiet reverence and wonder. What made these evenings transcendent was not the brilliance of any single dish, but the exclusive, cohesive progression that was shaped through the intimate dialogue between the two chefs—an unspoken conversation impossible to experience at Addison or Sézanne alone. In this collaboration, luxury revealed its rarest form: not extravagance, but the rare privilege of witnessing two masterful minds—united by their aligned philosophy, precision, and profound fluency with multicultural ingredients—truly elevate one another.

Chef Bradley’s "Eggs and Rice" (Photo by Junko Y.)

Chef Calvert’s Tea Smoked Chicken Wing (Photo by Junko Y.)

This was far more than a meeting of two Three-Michelin-Star kitchens. Collaborations of this caliber are rare to begin with, but what unfolded between Addison and Sézanne marked a defining moment—an inflection point that will be referenced for years within the global Michelin community. It was a union not merely of prestige but of perspective, bringing together two chefs who, beyond their shared three-star status, hold the maximum three-knives distinction from The Best Chef Awards—a testament not to trend, but to enduring creative authority.

What made this encounter singular was the convergence of two sharply individualistic culinary languages—each forged through relentless refinement, yet shaped by entirely different geographies. One chef, by advancing the expression of California gastronomy, elevated a region of Southern California—long overshadowed in the fine-dining conversation—into a destination recognized by the world’s most seasoned gastronomes; the other built, in Tokyo, a restaurant defined by its unwavering respect for Japan’s ingredients, articulated through a perspective honed across global kitchens—an approach that quickly established it among Asia’s most influential dining rooms.

For this two-night engagement, the guest list reflected the magnitude of the moment: Chef Thomas Keller among them, alongside long-time Addison devotees and international Michelin diners who travel expressly for meals of this caliber.

Chef William Bradley, who secured Southern California’s first Three-Michelin-Star distinction in 2022, opened Addison in 2006 with a conviction few shared at the time. San Diego had yet to be recognized as a fine dining destination, but Chef Bradley pursued his vision with quiet, unwavering focus—ultimately reshaping how the region is perceived in the world of haute cuisine.

Chef Daniel Calvert followed a trajectory that spans London, New York’s Per Se, Paris’s Epicure, and Hong Kong’s Belon before opening Sézanne in 2021. The restaurant earned its first Michelin star almost immediately, ascended to three stars in 2025, and secured the number-one position on Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants in 2024—a testament to Chef Calvert’s rigor, creativity, and precision.

Here is a detailed look at a night with these two chefs—revealed course by course, ingredient by ingredient.

Addison's Dining Room (Photo by Junko Y.)

The Welcome Sequence

The opening bite, from the Sézanne team, was a 48 Month Aged Comté Cheese Gougère—a warm, delicately airy shell that released a deep, refined cheese aroma the moment it reached the palate. Its flavor was concentrated yet never heavy, carrying a savory elegance without tipping into saltiness; the interior remained softly tender, the exterior lightly crisp and feather-fine. A subtle touch of black pepper added just enough lift to sharpen the Comté’s elegance. The bite established a poised, calmly assured beginning to the evening.

Next arrived Shigoku Oyster, an oyster delicacy from Chef Bradley’s Addison. Cultivated by Taylor Shellfish Farms in Washington—Shigoku oysters are prized for their pristine, concentrated flavor and faint cucumber-like freshness. Here, the oyster was paired with chilled horseradish custard, finger lime, dill, green apple, and pickled strawberries preserved since spring. The combination created a remarkably clean and refreshing profile: the oyster’s purity meeting the grassy brightness of dill and the crisp tartness of green apple, punctuated by the citrusy pop of finger lime. The flavor opened with quiet clarity, then rose into a crystalline briny finish that carried cleanly across the palate.

48 Month Aged Comté Cheese Gougère (Photo by Junko Y.)

Shigoku Oyster (Photo by Junko Y.)

The Prelude—an introductory sequence of bites—continued with Chef Bradley’s Salmon “Nigiri.” A precisely shaped disk of cured salmon—composed to match the exact precise contours of the dashi meringue beneath it—was layered with a perfectly aligned shiso leaf and finished with freshly grated wasabi. Seeing a variation of the bite that had once struck me so deeply during my earliest visit to Addison—before the restaurant earned its three stars—felt unexpectedly personal. Coming from Tokyo, and as a daughter of a devoted executive chef, I remember sensing in that first “Nigiri” a profound shokunin spirit: precision, quiet discipline, and a reverence for ingredients that echoed the craftsmanship I grew up around. Even the placement of the shiso—an ingredient ubiquitous in Japan yet often added without deliberate consideration—signaled care, intention, and respect.

This evening’s rendition carried the same emotional resonance. The salmon expressed a pure, deep flavor; the wasabi contributed its characteristic sweet, aromatic sharpness; the shiso offered a clean herbal lift without overshadowing the fish. The dashi meringue dissolved seamlessly, supporting the salmon’s pristine oceanic essence. It remained one of Addison’s most discreetly brilliant compositions: a single bite that encapsulated the restaurant’s precision, philosophy, and craft.

Chef Calvert’s Ankimo followed—monkfish liver, long regarded as the “foie gras of the sea,” presented here with a gel of Chinese soy sauce and a lift of black vinegar. The bite arrived in a delicate, crisp shell shimmering with dark-ruby highlights. One taste, and the shock was immediate. Despite years of eating ankimo in various forms, I had never encountered a flavor profile remotely like this.

The Chinese soy sauce carried astonishing depth—nothing akin to typical Japanese varieties, but concentrated to a rare intensity, reminiscent of high-grade tamari or an artisanal sashimi shoyu. It held a clear note of fermentation, a poised interplay of amami and karami, and a faint, elegant bitterness. Tasted alongside the soy sauce and the subtle lift of black vinegar, the monkfish liver expanded into an almost architectural richness, revealing a completely new register of what ankimo can be—intense, commanding, yet perfectly restrained.

The Prelude concluded with Chef Bradley’s Chicken Liver Churro, dusted with toasted cinnamon and paired with bitter Mexican chocolate, its crisp exterior encasing a velvety chicken-liver mousse. The clever juxtaposition with the monkfish liver bite was notably effective—a land-driven counterpoint to the sea-driven intensity that preceded it. The churro’s crackling shell opened into a mousse of deep, savory richness, carrying a subtle gaminess that was heightened by the warmth of cinnamon and the refined bitterness of the chocolate.

Despite originating from two distinct three-star kitchens, the progression felt seamless: two expressions of liver, each singular in form and expression, yet aligned in depth, focus, and craft. The two bites became a dialogue—monkfish liver articulated through Chef Calvert’s Asian culinary inflections, and chicken liver reimagined through Chef Bradley’s Southern Californian lens—yet neither overshadowed the other. Instead, they formed a cohesive statement about flavor, balance, and extraordinary craftsmanship.

What set these opening bites apart was not simply their precision but their lingering aftertaste—the way each offered a steady build of depth and authenticity without ever tipping into excess. Many fine-dining kitchens open with marked restraint, keeping flavors so light in an effort not to overshadow later courses that the first bites can feel tentative rather than expressive; others open with bold strokes that risk announcing themselves too loudly, too soon. Here, each bite asserted its identity from the beginning, then deepened as it continued across the palate. The aftertastes were distinct yet never heavy—resonant without feeling insistent, settling with an unforced majesty.

To achieve boldness without weight, richness without residue, and clarity without compromise requires a rare level of control. These chefs demonstrated that mastery with the very first bites—signaling the precision, harmony, and imagination that would define the courses to come.

Salmon “Nigiri” (Photo by Junko Y.)

Ankimo (Photo by Junko Y.)

Chicken Liver Churro (Photo by Junko Y.)

The Main Savory Sequence

Just as I was recalling the kanpachi preparation from my previous visit, Chef Bradley’s Sake Cured Kanpachi arrived—a composition with seasonal Asian pear, fermented-sake sorbet, and shiso in its leaf and blossom forms. Presented in a chilled, perfectly transparent glass, the dish mirrored its vessel: pristine, cool, and quietly luxurious. The opening taste carried a poised ginger note that met the kanpachi’s subtle marine sweetness, amplified by the supple, almost playful texture of the jelly. Ginger and kanpachi are a natural harmony, but the sake sorbet introduced an entirely different register—icy, aromatic, and unexpectedly multidimensional. Beneath the clarity of the flavors were discreet layers: the pear’s crisp, aqueous crunch; the faint fruitiness woven into the sorbet; a sweetness so carefully governed that it never drifted toward dessert. Instead, the sake’s gentle sweetness seemed to illuminate the fish’s own inherent, ocean-derived sweetness. The interplay of these distinct forms of sweetness—marine, botanical, fermented—was calibrated with exceptional precision, every detail expressed in a clean, measured pianissimo, a quiet overture hinting that a new phase was beginning.

From Chef Calvert’s Sézanne team, the next course featured Hokkaido Botan Ebi—one of the most prized shrimp served as sashimi, distinguished not only by its generous size and firmer texture compared to ama ebi, but also by its deeper umami and more pronounced oceanic amami. Here, it was paired with fresh sudachi, a cucumber sauce, and a lacquer of N25 Reserve Caviar, with a small shard of sudachi placed delicately on top. Sudachi, the diminutive citrus grown predominantly in Tokushima, contributed its concentrated, crystalline aroma—bright and incisive, yet softened by a gentle roundness—long appreciated in Japan for enhancing the flavor of delicately prepared washoku dishes.

The botan ebi’s natural sweetness, already resonant and full, was heightened by the cool vegetal character of cucumber and a whispered mint-like herbal lift. A subtly smoky, creamy base introduced an extra layer of dimension to the dish, while the sudachi’s controlled presence kept each bite taut and vibrant. When the shrimp’s layered sweetness met the clean, saline depth of the N25 caviar, the result was striking—a compact mouthful radiating layers of pure, measured elegance.

Sake Cured Kanpachi (Photo by Junko Y.)

Botan Ebi (Photo by Junko Y.)

Then came the moment I had been anticipating since my previous visit: Chef Bradley’s N25 Reserve Caviar—his signature dish, often affectionately called “eggs and rice.” At its core is Koshihikari rice, but in a rendering of unusual depth, bound with smoked sabayon and lifted by a toasted golden-sesame aroma. The interplay is remarkable: a warm, delicately smoked foundation that broadens into the caviar’s cool salinity, all held together by the gentle, natural sweetness of Koshihikari. “This is the best dish I’ve ever had in my life,” a guest at the neighboring table exclaimed earlier in the evening—and I understood the sentiment instantly. The dish has drawn guests to Addison for nearly four years, counting its earliest iteration, well before the restaurant attained its third star.

What is truly astonishing is the degree of thought invested into refining such a familiar grain. Koshihikari is one of Japan’s most ubiquitous types of rice—high in starch, comforting, and deeply woven into everyday meals—yet its simplicity makes it surprisingly unforgiving. Its sweetness is delicate and highly specific; the wrong kind of creaminess can smother it, leaving the palate fatigued. This is why pairing Koshihikari with European-style creamy sauces is generally eschewed in Japanese cuisine.

Yet Japan is no stranger to rich, viscous accompaniments for rice: consider tororo, the grated Japanese yam—airy, silky, lightly sticky—traditionally spooned over a bowl of hot rice. The issue has never been texture or richness; it is alignment. Koshihikari accepts certain forms of creaminess and rejects others. It may appear like a blank canvas, but it has its own quiet preferences.

N25 Reserve Caviar (Photo by Junko Y.)

This is what makes Chef Bradley’s interpretation so striking. Sabayon—a European sauce with a mousse-like, velvety structure—should not pair naturally with Koshihikari, yet his smoked rendition finds an astonishing point of balance. Its refined smokiness, with the subtle acidity, amplifies the rice’s amami without overwhelming it, producing a coherence that feels inevitable only after you taste it. Achieving such calibration requires an unusually perceptive palate and a deep understanding of both cuisines. Crowned with a generous layer of caviar—not ikura—the dish becomes unmistakably his own invention.

It is, without question, a signature worthy of three Michelin stars—one that lingers in memory long after the meal, prompting many guests to return to Addison for this plate alone.

What followed reinforced the sense of continuity that threaded the entire menu. Despite the collaboration between two chefs, the progression again carried a quiet cohesion that felt entirely natural. The sequence of marine-driven dishes—kanpachi, botan ebi, then caviar—created a natural current, and the repeated appearance of N25 Reserve Caviar, first in Chef Calvert’s botan ebi course and again in Chef Bradley’s signature, formed a thoughtful bridge between their styles.

From Addison came the next course: Steamed Amadai in a delicate shellfish consommé with matsutake, battera kombu, and wakame. As the bowl was set down, a gentle, aromatic plume of consommé rose upward—clear in appearance yet quietly expressive. Its amber color suggested intensity, though the broth remained refined rather than assertive. Depending on the day’s shellfish, the kitchen sometimes refers to it as a crab consommé; on this evening, botan ebi shells formed its base, creating a thoughtful thread of continuity with Chef Calvert’s earlier dish.

Chef Bradley’s consommé is particularly focused, drawing a clean, concentrated dashi depth from the shellfish. Its finesse provided exactly the right frame for the amadai itself—sashimi-grade, handled with precision, and cooked with exceptional care. The center remained just shy of raw, preserving that gentle sweetness and oceanic aroma familiar from amadai sashimi.

The supporting elements added clear, expressive nuance. The wakame was beautifully refined, carrying a distinct oceanic flavor that intertwined seamlessly with the sweetness of both the fish and the broth. Battera kombu contributed a gentle, briny lift, while the interplay of textures—the supple amadai, the silken slip of the wakame—created a quietly intricate structure. I especially appreciated that Chef Bradley identified the seaweeds individually when presenting the dish. In Japanese cuisine, seaweed ingredients such as wakame, kombu, nori, and hijiki hold different roles and nuances, and acknowledging them by name reflects both understanding and respect.

The inclusion of matsutake—a highly prized Japanese mushroom—signaled clear seasonal intention. Tasted on its own, it carried its familiar deep, earthy perfume, yet once folded into the amadai, wakame, and consommé, its character diminished more than I personally wished. This reflects less a flaw than a difference in cultural expectation: in Japan, autumn kaiseki presents matsutake with a more overt, celebrated presence, and I instinctively look for that same abundance. Here, the mushroom was integrated more subtly as a seasonal note.

What lingered most was the fish itself. Coming from Japan, I know how rare it is to encounter a cooked fish executed with this level of precision—and this amadai achieved it. The temperature, texture, and flavor were all in perfect alignment, allowing the natural sweetness and purity of the fish to shine at its fullest expression. Supported by the wakame, battera kombu, and shellfish consommé, the dish resolved in complete harmony—an instance of technique and ingredient meeting with remarkable clarity and respect.

The next composition from Chef Calvert arrived as an Abalone Liver Parfait with roasted chicken-skin gelée scented with tarragon and lemon verbena, accompanied by gently prepared peanuts and a warm buckwheat scallop blini. What followed was less a sequence of flavors than an immediate gravitational pull: a depth so concentrated it resisted conscious interpretation in the moment. The awabi’s liver held an articulate, architectural bitterness—elegant, tightly framed, never austere. The chicken-skin gelée, already potent on its own, joined the abalone in a way that amplified both: oceanic and land-driven umami layered in complexity yet so perfectly integrated that it felt deeply singular, a flavor expression unlike anything I’d encountered. For a brief moment, language yielded to sensation; the palate registered something vast, intricate, and complete.

The scallop blini, warm and carrying a roasted kobashii oceanic sweetness, introduced a gentler register—its soft interior echoing the parfait’s velvety texture while its crisp edge offered just enough contrast to keep the bite lively. The peanuts extended that roasty aroma with a playful crunch, offering textural dimension without distraction. Remarkably, the finish dissolved with absolute cleanliness, leaving no weight, no harshness—only a long, disciplined echo of flavor control that seemed almost improbable.

A shift in cadence followed with Chef Bradley’s Sourdough Bread—a deliberate interlude in the arc of the meal. Five and a half years of nurturing its starter had yielded a loaf with a measured, confident acidity. The crust cracked with gentle crispness; the interior remained tender and fragrant. Two butters framed the pause: a nearly weightless goat’s-milk butter and a browned honey butter with subtle caramel notes. An intentional decrescendo, it acted as a luxurious moment of reset before the final ascent of the savory courses.

Steamed Amadai (Photo by Junko Y.)

Sourdough Bread (Photo by Junko Y.)

Abalone Liver Parfait (Photo by Junko Y.)

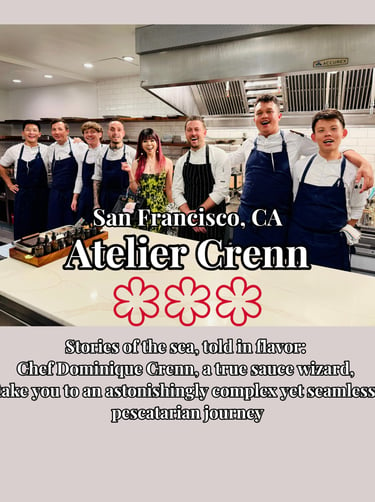

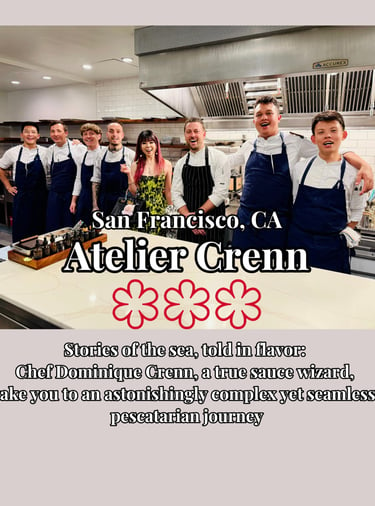

That ascent first came from Chef Calvert’s Sézanne team: a Tea Smoked Chicken Wing filled with Shanghai hairy crab. The shift back to complexity felt immediate. The skin—paper-thin, flawlessly intact—carried a subtle smoky nuance that was more akin to the aromatic warmth of historic Chinese banquet kitchens. Inside, peak-season kegani offered sweetness at its highest expression. A red pepper and crab-roe cream sauce, airy yet vivid, introduced a polished Chinese inflection filtered through French structure. Despite its orange-crimson hue, the sauce remained poised and deeply umami-driven rather than spicy, its smoky undertone far removed from the common char-driven profiles in California. Every detail—the crispness of the skin, the delicacy of its handling, the inimitable smokiness, the measured opulence of the sauce—spoke of arresting precision. The dish quietly summoned a faint nostalgia for the formal Chinese banquets of my distant memory, an emotion as unexpected as it was transporting.

Though I was tasting Chef Calvert’s dishes for the first time, this course and the Abalone Liver Parfait left the deepest emotional imprint—two compositions of dizzying complexity and imagination that shattered every expectation. Their level of execution was almost overwhelming in its perfection; the control and vision behind them so compelling that one truth became undeniable: I need to experience the full Sézanne tasting menu, and soon.

Tea Smoked Chicken Wing (Photo by Junko Y.)

Olive Wagyu (Photo by Junko Y.)

The final savory course was Chef Bradley’s A5 Olive Wagyu, served with caramelized shoyu and kinuta maki. The beef itself—known formally as Shodoshima Olive Gyu—has an origin story that mirrors the dedication behind the dish. Created on the small island of Shodoshima in Kagawa Prefecture, the wagyu is the result of more than two decades of passion and effort by cattle farmer Masaki Ishii. His mission began with frustration: Sanuki Ushi, the local breed, lacked the prestige of Kobe or Matsusaka beef. Determined to elevate it, Ishii centered his work on boosting oleic acid, the source of wagyu’s signature umami. Shodoshima, Japan’s leading olive producer, then offered an unexpected solution: olives contain naturally high levels of oleic acid. By incorporating olive pomace into the cattle feed, he developed beef with both rich marbling and a remarkable sappari—light, clean—finish.

The result is a wagyu unlike the typically weightier styles that often fatigue the Japanese palate when served in steak form. Olive Gyu holds depth without heaviness, richness without cloying oiliness, and a tenderness that remains lifted rather than dense. In Chef Bradley’s hands, this unique character was brought to its fullest expression. The exterior carried a crackling charcoal smokiness that countered the marbled interior with precision; every bite felt calibrated, intentional, and deeply satisfying.

Caramelized shoyu provided a sweet, lightly acidic counterpoint that complimented the beef’s richness with refined balance. A touch of yuzu kosho added a clean, aromatic nuance, and the kinuta maki introduced a fresh, raw, crisp vegetal contrast—a subtle but essential counterweight to the wagyu’s assertive richness.

As someone whose palate often tires of heavily marbled wagyu in steak form, this iteration felt exceptional. It was, without question, one of the most compelling executions of wagyu steak I have encountered. To experience beef born from a single producer’s decades-long pursuit and shaped with such technical clarity and care by Chef Bradley, gave the course an emotional and culinary completeness—a fitting, impeccably composed conclusion to the savory progression.

The Desserts

The dessert progression began with a Yuzu Custard tucked beneath a finely whisked layer of ceremonial matcha. Kiwi added a precise, almost glinting acidity, while the matcha’s composed bitterness grounded the citrus in quiet elegance. Together, they formed a refreshing interlude—purposeful, not merely palate-cleansing—and set the cadence for the sweets to follow.

From Sézanne came the Hot Chestnut Sabayon—a warm chestnut tart, finished tableside with a snowfall of Alba white truffle. Its aroma rose in slow, luxurious waves—woodland warmth, soft sweetness, and a faint, liqueur-like depth within the chestnut. In Japan, this season is marked by an abundance of chestnut confections across pâtisseries and confectionery shops, a cultural rhythm of autumn. Here, the tart occupied a distinct, rich register of its own: chestnut and Alba white truffle meeting in a poised, finely calibrated harmony that expressed the season with remarkable lucidity and elegance.

Yuzu Custard (Photo by Junko Y.)

Hot Chestnut Sabayon (Photo by Junko Y.)

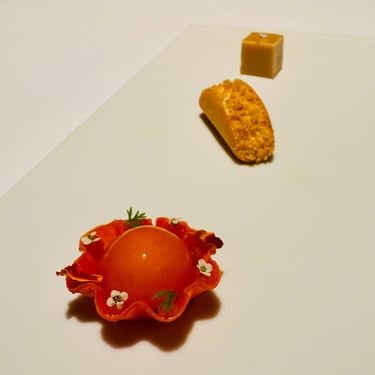

A plate of “Sweet Treats” then transitioned the evening into a more whimsical key.

Addison’s Carrot Cake “Tartlet” led the trio—a small, amber-bright composition whose lacquered surface gave way to a spiced cheesecake core. The flavor was concentrated yet buoyant, channeling the season’s aromatics without slipping into heaviness.

The mood shifted again with Addison’s Everything Lemon “Taquito,” its form a crisp, bite-sized hard-shell fold filled with lemon chantilly, custard, and crumble. The first bite broke with an elegant snap, releasing cool, vibrant citrus. Its brightness reset the palate with intention, creating a moment of lift before the finish grew deeper.

That depth arrived in Sézanne’s White Truffle Fudge. Presented as an understated, minimalist-look cube, it delivered an intensity that was startling in the most deliberate way: profoundly aromatic, smooth to the point of silkiness, and lingering with a deep, almost narcotic truffle resonance. It hovered long after the bite dissolved—an uncompromising, glorious surge of perfume and sweetness that refused to fade.

The evening concluded with Chef Bradley’s “Sweet Dreams,” his interpretation of Champurrado layered with whipped horchata, bitter orange, and candied coriander. Warm, fragrant, and quietly complex, it wove together chocolate richness with floral and spice-driven lift—clove, star anise, coriander, roasted cinnamon—each note rising and falling with measured cadence. A reimagined Mexican chocolate drink, it offered a thoughtful, composed finale: comforting, intricate, and entirely assured.

Carrot Cake “Tartlet,” Everything Lemon “Taquito,” White Truffle Fudge (Photo by Junko Y.)

Champurrado (Photo by Junko Y.)

The Service

Addison’s service remains one of the most fully realized expressions of Michelin-level hospitality in the United States, distinguished by a distinctly Californian warmth that feels authentically people-oriented. Chef Bradley and his team have an exceptional ability to make each guest feel recognized, valued, and remembered—an ease that stems not from informality but from mastery.

What sets their approach apart is the sense of breathing room woven into their service rhythm. In some elite dining rooms, I can feel a kind of professional tension—a near-visible pressure that shapes every step from kitchen to table. Expressions, pacing, and choreography often convey an unspoken urgency, the natural byproduct of teams operating at the apex of exactitude, where the margin for error is narrow and the evening unfolds like a live performance demanding impeccable timing. Still, as a guest, I inevitably absorb some of that intensity; though never the staff’s intention, it can make complete relaxation elusive and turn a simple question into an intrusion—not because the team is unwelcoming, but because their focus is calibrated so tightly to the demands of service.

California, however, has its own cultural cadence—open, warm, and grounded in genuine connection—and Addison embodies that sensibility as effortlessly as it expresses the state’s gastronomy. It is one of the three-star dining rooms where I never feel the invisible pressure of the brigade behind the scenes. I can settle into the experience without any sense of tension. No one on the Addison team, including Chef Bradley, has ever made me feel that a question disrupts the flow. Their calm is not casualness; it is discipline so refined it reads as ease.

The choreography is internalized to such a degree that it becomes nearly invisible. Plates arrive with quiet synchronicity—never rushed, never uncertain, never incongruent from one guest to another. Descriptions of the dishes are balanced and precise. When questions arise, the answers are thoughtful, measured, and warm—informative without the faintest note of hurry.

This trained elegance creates space for genuine personality to surface. The complexity and pressure mirror that of any three-star kitchen, yet the atmosphere feels remarkably unforced. That warmth becomes part of the experience itself—an undercurrent that brings intimacy to a tasting menu of great technical refinement.

One moment in particular captured their ethos. A server paused long enough to ask a pair of unexpected, reflective questions about my experience—questions that invited thought rather than rote affirmation. In a context where conversation often follows predictable patterns with “How is everything?” the gesture felt sincere and personal. Even in the midst of service, he created a small space for genuine conversation, not mere hospitality choreography. It felt meaningful.

The consistency of this service—its mastery, grace, and warmth—remains a key reason I continue to return.

The Final Thought

The collaboration dinner exceeded every expectation I brought into the room. Despite being shaped by two firmly established chefs from different countries—each with distinct training, instincts, and creative vocabularies—the evening unfolded with an almost uncanny sense of coherence. The progression was fluid, measured, and deliberate, never allowing one perspective to eclipse the other. That equilibrium is astonishing when considering how singular their approaches are: two chefs who command their own worlds, yet meet at the intersection of discipline, ingredient fluency, and technique honed to a razor’s edge.

The true alchemy of the night lay not in the individuality of the plates, but the way their voices intertwined. The refinement, structural complexity, and long, resonant finishes of each course revealed a shared rigor—an alignment of values that shaped a menu existing solely for these two nights. It was not something one could experience at Addison or Sézanne independently, but a rare intersection of two deeply articulate culinary minds.

Witnessing that rare, almost private dialogue between the chefs—expressed through their refined crafts—felt both incredibly fortunate and unmistakably energized—an emotion that carried through long after the final course. The dialogue between plates felt intimate and intentional, as if each chef were quietly finishing the other’s sentences. Transitions that could have felt abrupt instead became moments of revelation; flavors passed the baton with quiet assurance, creating a through-line of trust and respect. It was a rare kind of luxury—one born not of extravagance, but of two masters truly elevating one another.

Experiences like this deepen one’s understanding of a chef’s work. I left the evening with a renewed conviction that I must return to Tokyo to experience Chef Calvert’s full expression at Sézanne without delay.

Next year marks Addison’s twentieth anniversary, followed by a remodeling of its beloved dining room in the spring. There is a touch of bittersweetness in knowing the room that has held so many remarkable memories will evolve—but also an undeniable sense of anticipation for what its next chapter will bring.

Without hesitation, this evening stands among the most extraordinary Michelin-level experiences of my dining life—rare, resonant, and utterly unforgettable.

Visited: November 10, 2025